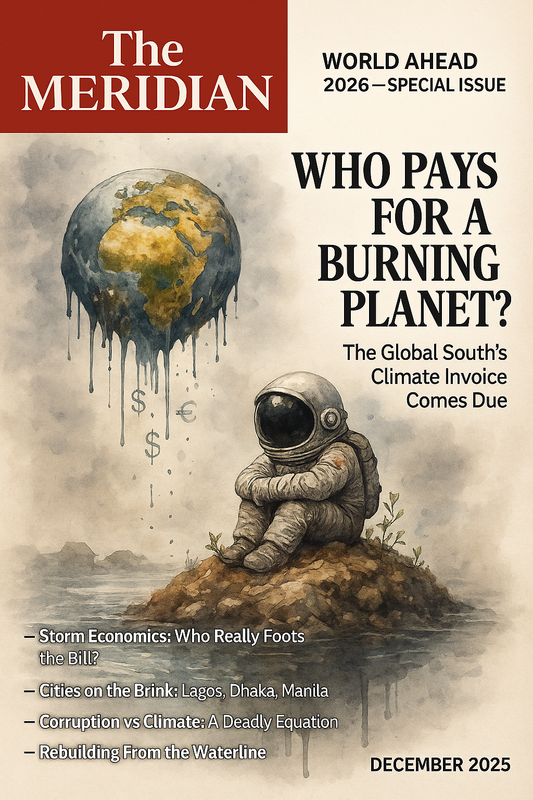

Who Pays for a Burning Planet?

Climate Risk, Debt & the Global South's New Vulnerability Economy

In August 2022, Pakistan received one-third of its annual rainfall in a single month. Thirty-three million people were displaced. Infrastructure worth over $30 billion was destroyed. The government, already servicing external debt equivalent to 77 percent of GDP, borrowed $1.1 billion from the IMF for emergency relief. That loan came with conditions: freeze public sector wages, cut subsidies, raise electricity tariffs. Two years later, Pakistan is still repaying that debt—at commercial rates, to creditors in countries whose historical emissions are forty times higher per capita.

This is not climate finance. This is climate billing. And it is how the world actually handles the costs of a burning planet: by converting weather disasters into sovereign debt, austerity programmes, and regressive taxation that falls hardest on those who contributed least to the crisis.

Annual climate-related losses now reach $200–300 billion globally, affecting infrastructure, agriculture, housing, and livelihoods across the tropics and sub-tropics. Yet the Loss and Damage fund—established after three decades of negotiation at COP28—attracted just $700 million in initial pledges. That represents 0.2 percent of developing countries' estimated annual adaptation and loss needs, which the UN Environment Programme places between $215 billion and $387 billion by 2030.

The arithmetic is brutal, but the politics are clear. Someone is already paying for climate change. The question is not whether the bill exists, but whose name appears on the invoice—and with what power to refuse payment. The Global South is discovering that climate vulnerability is being monetised through debt markets, creating what this analysis terms the vulnerability economy: a system where environmental shocks are converted into financial obligations, binding nations into permanent cycles of borrowing, repayment, and reduced capacity for resilience.

How Climate Disasters Become Sovereign Debt: Four Case Studies

The conversion of climate shocks into debt obligations follows predictable patterns. Four recent examples illustrate the mechanism with precision.

Pakistan 2022: When monsoon floods displaced 33 million people and caused $30 billion in damages (equivalent to 10% of GDP), Pakistan's external debt stood at $126 billion—77% of GDP. The government secured a $1.1 billion IMF Standby Arrangement in July 2023, followed by a $3 billion Stand-By Arrangement. Conditions included freezing public sector wages, removing energy subsidies, and raising the policy rate to 22%. Two years later, Pakistan services this debt while 40% of the flood-affected population remains in temporary shelter. The country now allocates more to debt service than to health and education combined.

Mozambique 2019: Cyclones Idai and Kenneth struck within six weeks, killing over 1,000 people and causing $3.2 billion in damages—equivalent to 20% of GDP. Mozambique, already in debt distress with external debt at 107% of GDP, borrowed $118 million from the IMF and $545 million from the World Bank. Reconstruction financing came primarily through external loans. By 2023, Mozambique was spending 54% of government revenue on debt service—nearly triple the allocation for health. The country entered formal debt restructuring negotiations in 2024.

The Bahamas 2019: Hurricane Dorian caused $3.4 billion in damages—equivalent to 25% of GDP, making it one of the costliest disasters relative to economic size in modern history. The Bahamas' public debt jumped from 59% of GDP in 2018 to 79% by 2020. The government issued a $300 million bond in 2020 at 8.95% interest—substantially higher than pre-disaster borrowing costs. Standard & Poor's downgraded the country's credit rating, raising future borrowing costs further. Six years later, debris removal is ongoing and housing reconstruction incomplete.

Madagascar 2021-2022: Severe drought in southern Madagascar created what the UN termed the world's first "climate change famine," affecting 1.3 million people. Madagascar, with external debt at 41% of GDP, secured $312 million in IMF emergency financing. The loan came with fiscal consolidation requirements, including civil service hiring freezes. Madagascar now faces recurring drought cycles while servicing external debt at rates that absorb 8% of government expenditure—more than the entire budget for agriculture in a country where 80% of the population depends on farming.

| Country (Year) | Disaster Cost (% GDP) | Pre-Disaster Debt/GDP | Post-Disaster Financing | Current Debt Service/Revenue |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan (2022) | $30B (10%) | 77% | $4.1B IMF loans + commercial borrowing | >40% (exceeds health + education) |

| Mozambique (2019) | $3.2B (20%) | 107% | $663M multilateral emergency loans | 54% (3x health budget) |

| The Bahamas (2019) | $3.4B (25%) | 59% | $300M bond at 8.95% + multilateral | Debt/GDP jumped to 79% by 2020 |

| Madagascar (2021-22) | Severe drought (unmeasured) | 41% | $312M IMF emergency financing | 8% of expenditure (exceeds ag budget) |

The Vulnerability Economy Explained

Traditional economics treats climate change as a negative externality—a side-effect requiring price adjustments. But across much of Africa, Asia, Latin America, and the island world, climate risk has fused with four structural constraints to create something more dangerous: a political-economic regime where each shock intensifies vulnerability rather than triggering resilience.

The vulnerability economy operates through a specific mechanism. Climate shocks hit economies already carrying high debt burdens and running large import bills for food and fuel. Governments respond with emergency spending financed by additional borrowing. That debt constrains future investment in adaptation infrastructure. The next climate event strikes a poorer, more indebted, more politically fragile society.

| Constraint | Mechanism | Climate Multiplier Effect |

|---|---|---|

| High Public Debt | Limited fiscal space for emergency response | Post-shock borrowing at elevated rates; debt-to-GDP ratios spike |

| Food & Fuel Import Bills | Foreign exchange vulnerability to global price shocks | Droughts/floods drive food imports; currency depreciates; inflation rises |

| Weak Fiscal Space | Limited revenue base; high external obligations | Cannot finance adaptation infrastructure; forced into emergency mode |

| Infrastructure Gaps | Inadequate drainage, sea walls, early warning, storage | Each shock destroys more; rebuilding absorbs scarce resources |

| Commitment | Promised | Delivered | Delivery Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copenhagen 2009: $100B/year by 2020 | $100B annually | ~$83B (2020), disputed methodology | 83% (if counting loans at face value) |

| Loss & Damage Fund (COP28 2023) | Needs: $215-387B/year | $0.7B initial pledges | 0.2-0.3% of need |

| Adaptation Finance (actual need) | $215-387B/year by 2030 | ~$20-40B current flows | 5-19% of need |

| Green Climate Fund (target) | $10B initial capitalization | $10.3B pledged, $8.2B received | 82% of pledges received |

| Category | Share | Issue |

|---|---|---|

| Loans | ~70% | Counted at face value, not grant-equivalent; adds to debt burden |

| Grants | ~25-30% | True concessional support, but insufficient for needs |

| Mobilized Private Finance | Claimed ~15-20% | Double-counting issues; follows commercial logic, not climate justice |

| Mitigation vs Adaptation | 60% mitigation, 30% adaptation | Mitigation attracts private capital; adaptation needs are underfunded |

| Multilateral vs Bilateral | 60% bilateral, 40% multilateral | Bilateral often tied to donor country contractors/exports |

The Language of Conditionality: What IMF Programmes Actually Demand

When a climate-shocked country turns to the IMF, the "support" comes with conditions. These are not abstract policy suggestions—they are binding requirements embedded in loan agreements. The language is technocratic, but the effect is concrete: austerity imposed on populations already suffering climate disasters.

Here is what IMF conditionality actually looks like, extracted from recent programmes in climate-vulnerable countries:

| Country & Programme | Actual Conditionality Text | Translation |

|---|---|---|

| Pakistan 2023 SBA (Post-flood) |

"Freeze nominal wages and pensions in the public sector... Increase the general sales tax rate from 17% to 18%... Eliminate subsidies on electricity and gas" | Public workers get no wage increase during 40% inflation. Poor pay more sales tax. Energy prices surge for households already devastated by floods. |

| Kenya 2021 ECF/EFF (Drought-affected) |

"Contain the public sector wage bill at 4.0% of GDP... Eliminate inefficiencies in the energy sector through cost-reflective tariffs" | Hiring freeze while climate shocks increase need for disaster response. Electricity prices rise during drought affecting food security. |

| Ghana 2023 ECF (Debt distress + climate vulnerability) |

"Remove fuel subsidies... Freeze wages in nominal terms... Increase VAT... Reduce exemptions on petroleum products" | Fuel costs spike for farmers and transport. Wages frozen. Regressive VAT hits food prices. Cumulative impact on poorest households: severe. |

| Madagascar 2021 ECF (Famine conditions) |

"Civil service hiring limited to 15% of departures... Strengthen cost recovery in public services" | Healthcare and education staffing cut during crisis. "Cost recovery" = user fees for services poor cannot afford. |

| Mozambique 2022 ECF (Post-cyclone) |

"Contain the wage bill... Improve efficiency in public spending... Advance energy sector reforms toward cost-reflective pricing" | Public sector capacity reduced while rebuilding needed. Energy prices rise for households displaced by cyclones. |

| Region/Country | Climate Vulnerability | External Debt/GDP | Debt Service/Revenue | Recent Climate Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | Extreme floods, heatwaves, glacial melt | 77% | >40% | 2022 floods: $30B (10% GDP) |

| Bangladesh | Cyclones, river flooding, sea-level rise | 42% | 22% | Annual floods 20-30% land area |

| Mozambique | Cyclones, droughts, coastal erosion | 107% | 54% | 2019: Idai + Kenneth $3.2B (20% GDP) |

| Ghana | Droughts, coastal erosion, irregular rainfall | 88% | 52% | 2023 default; climate shocks compound debt |

| Kenya | Droughts, flooding, locust swarms | 67% | 37% | 2022-23 worst drought in 40 years |

| Zambia | Droughts, erratic rainfall, hydropower dependency | 132% | Post-default restructuring | 2023 drought cut hydropower 70% |

| Sri Lanka | Floods, droughts, coastal vulnerability | 128% (pre-default) | Default 2022, restructuring | Climate + economic crisis = default |

| Small Island States (avg) | Existential threat (sea-level, hurricanes) | 60-100% | 30-50% | Annual hurricane rebuilding cycles |

| Country | 10-Year Bond Yield (approx) | Credit Rating | Climate Premium Estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pakistan | 12-15% (when market accessible) | CCC+ (S&P) | Climate risk adds 2-3% to spreads |

| Kenya | 10-12% | B (S&P) | Drought exposure cited in rating rationale |

| Mozambique | Market access lost (distress) | SD (S&P) | Cyclone history cited as structural weakness |

| The Bahamas | 8-10% | BB- (S&P) | Hurricane vulnerability explicit in downgrade |

| Ghana | Market access lost (default) | SD/RD | Climate + debt = default spiral |

| Barbados | 7-9% | B+ (S&P) | Hurricane exposure limits fiscal space |

The Arithmetic of Injustice

Strip away diplomatic language and the climate economy collapses into a balance sheet question: who absorbs the losses? The numbers reveal a system that subsidises fossil fuels more generously than it finances climate adaptation and loss compensation combined.

Developing countries (excluding China) may need $2.4 trillion annually by 2030 for climate investments and related development goals, according to UN-commissioned estimates. The adaptation finance gap alone—what is needed versus what flows—runs into hundreds of billions per year. Meanwhile, global fossil fuel subsidies (including the underpricing of environmental and health costs) reach into the trillions annually, with direct consumer and producer subsidies in the hundreds of billions.

But the deeper injustice lies in cumulative historical responsibility. Since the industrial revolution, the atmosphere has absorbed approximately 2,500 billion tonnes of CO2 from human activity. The distribution of that responsibility is stark and measurable.

| Country/Region | Cumulative Emissions (Gt CO2) | % of Global Total | Current Climate Finance Contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | ~420 Gt | ~25% | $11.4B (2022, OECD data) |

| European Union (27) | ~350 Gt | ~22% | $28.6B (2022, largest contributor) |

| China | ~235 Gt | ~14% | Recipient + South-South cooperation (~$3-4B/year) |

| Russia | ~115 Gt | ~7% | Minimal contributions |

| Japan | ~65 Gt | ~4% | $11.8B (2022) |

| India | ~55 Gt | ~3% | Recipient country |

| Sub-Saharan Africa (total) | ~45 Gt | ~2% | Recipient region |

| Small Island Developing States | ~2 Gt | <0.1% | Recipient, facing existential threat |

| Category | 2022 Value | 2023 Value (est.) | Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big Oil Combined Profits (Top 5) | $200B+ | $150B+ | ExxonMobil, Shell, BP, Chevron, TotalEnergies |

| Saudi Aramco Profit | $161B | $121B | World's most profitable company |

| Total Fossil Fuel Sector Profits | $4 trillion+ (est.) | $2.5-3 trillion (est.) | Includes coal, gas, petrochemicals |

| Global Climate Finance to Developing Countries | $83-100B | ~$100B | 70% loans, not grants |

| Loss & Damage Fund Pledges | N/A | $0.7B | 0.5% of Saudi Aramco profit alone |

| Fossil Fuel Subsidies (Global) | $7 trillion | $6.5 trillion (est.) | IMF figure includes environmental underpricing |

| Layer | Mechanism | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Historical | Countries with lowest cumulative emissions hit hardest by impacts | Africa (4% global emissions) faces severe droughts, floods, heat; Small Island States face existential threat |

| Financial | Climate-vulnerable states pay higher borrowing costs after shocks | Rating agencies treat climate vulnerability as credit risk, not basis for concessional support |

| Intergenerational | Future taxpayers service debt incurred for disasters they didn't cause | Youth in Pakistan, Mozambique, Caribbean inherit climate debt burdens from others' historical emissions |

Who Actually Pays Today?

The answer is empirical and specific. Four groups bear the primary burden of climate costs in the absence of adequate international finance.

Poor households and informal workers: The street vendor in Lagos, the garment worker in Dhaka, the smallholder farmer in Malawi. When droughts spike food prices or floods destroy housing, real incomes fall. Heatwaves reduce outdoor productivity. Vector-borne diseases rise. None of these losses appear in climate finance statistics. They are absorbed silently, reducing living standards and human capital.

Women and unpaid care: Climate shocks have a gendered dimension. When water sources are contaminated, women and girls walk further to fetch water, losing time for schooling or paid employment. When health systems are strained by climate-related disease, care falls disproportionately on female family members. As income volatility rises, girls face higher risks of early school withdrawal or early marriage in some contexts.

Future taxpayers: When governments borrow after disasters, the bill is passed forward. Future taxpayers in Pakistan, Mozambique, or the Caribbean will service loans taken to repair damage from climate shocks they did not cause. That servicing often happens through VAT, fuel taxes, and other regressive levies that hit lower-income households hardest. Climate debt becomes intergenerational taxation.

Migrants and displaced communities: People pay in movement. Millions are displaced annually by floods, storms, and droughts. For vulnerable coastal and island states, planned relocation is now on the agenda. The cost is social as much as financial: loss of land, culture, language continuity. This is climate payment in the currency of identity and belonging.

| Impact Channel | Mechanism | Household Cost Example |

|---|---|---|

| Food Price Inflation | Droughts/floods reduce harvests; imports rise | Pakistan 2022: wheat prices +60%, onions +140%; poor households spend 50-65% income on food |

| Productivity Loss (Heat) | Outdoor workers lose hours; illness rises | South Asia: 5-15% productivity loss in peak heat; equivalent to 10-30 days lost wages annually |

| Health Expenditure | Vector-borne disease, water contamination | Kenya floods 2023: cholera cases +300%; households pay out-of-pocket for treatment |

| Housing Reconstruction | Floods/storms destroy homes; rebuilding on own funds | Bangladesh: cyclone-affected households borrow $500-2,000 (informal lenders, 20-40% interest) |

| Water Fetching Time | Drought/contamination forces longer trips | Sub-Saharan Africa: women/girls spend 2-6 extra hours/day = lost education/income opportunity |

| Asset Liquidation | Sell livestock, tools, land to cope with shock | Ethiopia drought: 40% of affected households sold productive assets, reducing future income |

| School Withdrawal | Children pulled from school for income/care work | Mozambique post-cyclone: 30% rise in child school dropout in affected areas |

The Insurance Illusion and the Protection Gap

In theory, insurance spreads risk. In practice, as climate hazards intensify, private insurers are withdrawing from high-risk areas or dramatically raising premiums. In the United States, major insurers have scaled back coverage in wildfire-prone and hurricane-exposed states. Similar dynamics are emerging in island and coastal nations elsewhere.

In the Global South, where insurance penetration is already low, climate risk is increasingly uninsurable on market terms. This creates what insurers call the "protection gap"—the difference between total economic losses and insured losses, which remains very large in developing countries.

Who fills that gap? Not reinsurers. Not rating agencies. Not G7 climate summits. In practice, the protection gap is filled by households depleting savings, small farmers borrowing at high interest from informal lenders, governments postponing maintenance and cutting investment, and communities relying on unpaid care work—often by women—to absorb shock after shock. Insurance exits precisely where risk becomes systemic and structural. The market does not underwrite the Anthropocene.

| Actor | Mechanism | Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Private Insurance | Withdrawing from high-risk areas or raising premiums to unaffordable levels | Declining coverage in climate-exposed regions |

| Households | Deplete savings, sell livestock, pull children from school | Millions of families absorbing uncompensated losses |

| Informal Lenders | Small farmers borrow at high interest rates post-disaster | Debt traps deepen poverty cycles |

| Governments | Postpone maintenance, cut investment, raise regressive taxes | Fiscal space shrinks; adaptation underfunded |

| Women's Unpaid Care | Increased care work as health systems strain, water sources contaminated | Gender burden intensifies; lost productivity |

| Region/Market | Premium Change (2018-2023) | Coverage Change | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caribbean (Hurricane) | +200-400% | Major insurers withdrawing | Only 15-20% of disaster losses insured; rebuilding on government debt |

| Pacific Islands | +150-300% | Limited availability | Coverage gaps force reliance on donor assistance and remittances |

| Florida (USA) | +100-200% | Multiple insurer exits | State-backed insurer of last resort under strain |

| California Wildfire Zones | +50-150% | Non-renewals rising | FAIR Plan (state insurer) exposure jumped 70% |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | Low baseline penetration | Under 5% disaster coverage | Market failure: risk too high for commercial terms |

| South Asia | Agriculture: +40-80% | Under 20% smallholder coverage | Index insurance experiments show promise but remain limited |

How the Global North "Pays" for Climate Change

High-income countries claim to provide climate finance, but the accounting reveals three techniques that limit actual transfers:

Selective accounting: Official climate finance statistics count loans at face value, not grant-equivalent value. Existing development finance is relabeled as climate-aligned. Export credit and commercial flows are blended into climate tallies, inflating reported contributions.

Self-interested industrial policy: Green industrial packages in the United States and Europe—the Inflation Reduction Act, the Green Deal Industrial Plan—are framed as global climate solutions. But the bulk of public money is spent domestically to build national manufacturing, battery, solar, and hydrogen ecosystems. They may reduce global emissions, which is necessary. But financially, they do not pay for damage already inflicted on countries with limited historical responsibility.

Border carbon measures as cost-shifting: The European Union's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), which began its transition phase in October 2023, imposes tariffs on imports based on their embedded carbon emissions. By 2026, the system will be fully operational, covering cement, iron, steel, aluminium, fertilisers, electricity, and hydrogen. The EU frames this as climate policy, but the mechanism functions as a de facto tariff that protects European producers while taxing exporters from developing countries.

For a steel exporter in India or an aluminium producer in Mozambique, CBAM means: either invest billions in decarbonisation technology (financed how, exactly?) or pay the EU a carbon levy on every tonne exported. The revenue from that levy goes to the EU budget, not to climate finance for the exporting country. No technology transfer is mandated. No concessional finance is guaranteed. The adjustment cost falls entirely on the exporter.

The United Kingdom, Canada, and Japan are considering similar mechanisms. The United States has discussed carbon tariffs under various proposals. If implemented broadly, border carbon adjustments risk becoming a new form of trade protectionism—climate policy in name, industrial defense in practice. The Global South faces a choice: decarbonise at your own expense, or lose market access to wealthy consumers.

Carbon offset markets as accounting fraud: Voluntary carbon markets—where companies purchase "credits" from forest preservation or renewable projects to offset their emissions—grew rapidly in the early 2020s, reaching $2 billion in 2021. The promise was elegant: polluters pay, forests are protected, everyone wins. Reality proved otherwise.

Multiple investigations exposed systematic problems. A 2023 analysis by The Guardian, Die Zeit, and SourceMaterial found that more than 90% of rainforest carbon offsets approved by Verra—the world's leading certifier—were likely "phantom credits" that did not represent genuine carbon reductions. Projects claimed forests were under threat that were never at risk. Baselines were manipulated. Leakage went uncounted (when protection in one area simply shifted deforestation elsewhere). Indigenous communities whose land generated credits often received minimal compensation.

By 2023, the voluntary carbon market had collapsed to under $1 billion, down 60% from its peak. Major buyers—including Shell, Gucci, and Delta—quietly stopped making offset claims after investigations. But the damage was done: for years, companies used cheap, fraudulent credits to claim "carbon neutrality" while actual emissions continued rising. The Global South provided the land, the forests, and the veneer of climate action—while Northern companies profited from green branding without meaningful emissions cuts.

| Year | Market Value | Key Events/Scandals |

|---|---|---|

| 2019 | $300 million | Market expansion begins |

| 2020 | $500 million | COVID stimulus includes carbon offset enthusiasm |

| 2021 | $2 billion (peak) | Corporate net-zero pledges drive demand; prices surge |

| 2022 | $1.9 billion | South Pole (major developer) exposed for overstating protections |

| 2023 | $720 million (-60%) | Guardian/Die Zeit investigation: 90%+ Verra credits "phantom"; major buyers exit |

| 2024 | ~$500 million (est.) | Regulatory scrutiny increases; corporate claims collapse |

| Country/Region | Sector Exposed | Export Value at Risk | CBAM Levy Estimate (Annual) |

|---|---|---|---|

| China | Steel, aluminium, cement, fertilisers | ~€20-25 billion | €1.5-2 billion (depends on carbon pricing) |

| India | Steel, aluminium | ~€3-4 billion | €200-300 million |

| Turkey | Steel, cement | ~€2-3 billion | €150-250 million |

| Russia | Steel, aluminium, fertilisers | ~€5-7 billion (pre-sanctions) | Significant but trade disrupted |

| Ukraine | Steel, fertilisers | ~€1-2 billion | €100-150 million |

| Mozambique | Aluminium | ~€400-600 million | €30-50 million (significant for economy) |

| South Africa | Steel, aluminium | ~€800 million-1 billion | €60-80 million |

The Invisible Polluters: Military Emissions Excluded from Climate Accounting

The Paris Agreement requires countries to report national greenhouse gas emissions. But one category remains systematically excluded: military emissions. Under pressure from the United States during the 1997 Kyoto Protocol negotiations, military fuel use and operations were made optional in national reporting. That exemption persists.

This is not a minor footnote. The US military alone—the world's single largest institutional consumer of petroleum—emits more CO2 annually than entire countries. Conservative estimates place US military emissions at over 50 million tonnes of CO2 per year, equivalent to the total emissions of Sweden or Portugal. Some studies suggest the true figure, including supply chains and base infrastructure, could exceed 200 million tonnes.

Global military emissions remain poorly documented, but available evidence suggests they account for 5-6% of global greenhouse gas emissions—roughly equivalent to the entire aviation sector. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan alone are estimated to have generated over 400 million tonnes of CO2, more than the annual emissions of 140 countries combined. The war in Ukraine, with its fuel-intensive armour, artillery, and infrastructure destruction, adds tens of millions of tonnes annually that appear in no national inventory.

For context: Pakistan, which bore $30 billion in climate disaster costs in 2022, emits roughly 250 million tonnes of CO2 annually—total, across its entire economy of 240 million people. The US military's emissions alone represent 20-40% of Pakistan's total, yet they are excluded from climate negotiations, finance calculations, and historical responsibility accounting.

This exclusion is not accidental. It is structural. The five permanent members of the UN Security Council—the United States, China, Russia, France, and the United Kingdom—are also the world's five largest military spenders and among the largest arms exporters. Counting military emissions would require transparency about operations, force posture, and fuel logistics that militaries consider strategic secrets. It would also expose the carbon cost of power projection—the ability of wealthy nations to deploy force globally while demanding emissions cuts from developing countries.

| Country/Conflict | Estimated Annual Emissions | Comparison | Reporting Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| US Military (annual) | 50-200 million tonnes CO2 | Equivalent to Sweden or Portugal (50M) to Peru (200M) | Partially reported, supply chains excluded |

| China PLA (estimated) | 40-100 million tonnes CO2 | Growing rapidly with force modernization | Not transparently reported |

| Russia Military (annual) | 25-50 million tonnes CO2 | Increased significantly during Ukraine war | Minimal transparency |

| NATO (total annual) | ~250 million tonnes CO2 | Equivalent to total emissions of Pakistan | Member states report inconsistently |

| Iraq War (2003-2011 total) | ~250 million tonnes CO2 | Not counted in US climate commitments | Never included in UNFCCC submissions |

| Afghanistan War (2001-2021) | ~200 million tonnes CO2 | More than 140 countries' annual emissions | Excluded from Paris Agreement accounting |

| Ukraine War (2022-2024 est.) | 100+ million tonnes CO2 | Includes fuel, infrastructure destruction, reconstruction | Not counted in any national inventory |

| Global Military (annual total) | ~1.2 billion tonnes CO2 (est.) | 5-6% of global emissions, equivalent to aviation sector | Largely unreported |

COP30 in Brazil: The Reckoning Postponed or the Turning Point?

In November 2025, the world convenes in Belém, Brazil for COP30—the thirtieth Conference of the Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change. The choice of venue is symbolic: Belém sits at the mouth of the Amazon, the river system that regulates planetary climate but is being destroyed at a rate of one football pitch every two minutes. Brazil's President Lula has framed COP30 as the "COP of the Amazon," promising to centre Indigenous voices and forest preservation.

But the real negotiations will determine something more fundamental: whether the vulnerability economy becomes permanent, or whether a new financial architecture emerges. Five issues will define whether COP30 is remembered as a turning point or another exercise in diplomatic theatre.

1. The New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on Climate Finance: The $100 billion annual target established in 2009 formally expires in 2025. COP30 must agree on a new finance goal. Developing countries are demanding $1-1.3 trillion annually—a figure grounded in actual needs for mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage. Developed countries have not yet put a number on the table. Early indications suggest they will propose a target in the $200-300 billion range, with heavy reliance on "mobilised private finance" that counts loans and investment that would have happened anyway.

The gap between $1 trillion and $200 billion is not a rounding error. It is the difference between a financial system that enables adaptation and one that perpetuates debt.

2. Loss and Damage Fund Operationalisation: The fund exists on paper. COP30 must determine: Who contributes? How much? On what schedule? Will it be grants or loans? Who can access it, and how quickly? Will it require IMF-style conditionalities? The initial $700 million pledged at COP28 was a symbolic down payment. If COP30 fails to establish a credible capitalization mechanism—ideally reaching $20-50 billion annually by 2030—the fund will remain a diplomatic fig leaf.

3. CBAM and Trade-Climate Linkages: By COP30, the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will have been operational for over a year. Developing countries will arrive with evidence of its impact on their export revenues and industrial competitiveness. Brazil, India, South Africa, and China are coordinating a joint position demanding that any border carbon measures be accompanied by technology transfer, concessional finance for industrial decarbonisation, and revenue redistribution. If COP30 fails to address CBAM, expect unilateral retaliation—carbon tariffs imposed by the Global South on Northern exports of financial services, pharmaceuticals, or high-tech goods.

4. Fossil Fuel Subsidy Reform and "Phase Down": COP28 in Dubai produced the first-ever agreement mentioning "transitioning away from fossil fuels." But fossil fuel subsidies remain untouched, running into hundreds of billions of dollars annually. COP30 in Brazil—a country that has resisted oil exploration in the Amazon under Lula but faces domestic pressure to exploit offshore reserves—will test whether the Global South can demand subsidy cuts from OECD countries as a condition for accepting emissions reductions. If wealthy nations continue subsidising oil and gas while demanding that Kenya or Senegal abandon their discoveries, the hypocrisy will be undeniable.

5. Amazon Debt-for-Nature and Indigenous Rights: Brazil is proposing large-scale debt-for-nature swaps where creditors forgive debt in exchange for Amazon preservation commitments. This could restructure tens of billions in sovereign debt across Latin America. But the mechanism raises questions: Who certifies compliance? Do Indigenous communities have veto power over land use? Can debt relief come with conditions that constrain future development? If done right, this could pioneer a new model. If done wrong, it becomes "green colonialism"—wealthy countries buying control over Global South resources under the guise of climate action.

| Issue | Global South Demand | Global North Position | Likely Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Finance Goal (NCQG) | $1-1.3 trillion/year in grants | $200-300 billion, heavily reliant on "mobilised" private finance | Compromise $400-600B, ambiguous on grant/loan split |

| Loss & Damage Fund | $20-50 billion/year, grants, fast access | Voluntary contributions, unspecified amounts | $5-10 billion pledges, access mechanisms unclear |

| CBAM & Border Measures | Technology transfer + revenue sharing + decarbonisation support | Maintain CBAM, minimal support | Stalemate; issue deferred to trade forums |

| Fossil Fuel Subsidies | Phase out all subsidies by 2030 | No binding commitment | Aspirational language, no enforcement |

| Debt-for-Nature | Creditor-funded, Indigenous-led, no new conditionalities | Case-by-case, market-based, verification required | Pilot programmes, limited scale |

| Military Emissions | Mandatory reporting in NDCs | Maintain current exemption | No change; exemption continues |

Three Futures for the 2030s

The answer to "who pays" is not fixed. It will be shaped by choices over the next 5–10 years. Three trajectories suggest themselves, each with distinct political and economic consequences.

Key Features:

- Loss & Damage scaled to tens of billions annually with automatic triggers and grant-based disbursements

- Significant SDR re-channeling to climate-vulnerable countries at concessional rates

- Debt-for-climate swaps move from boutique deals to system-level instruments

- Rating agencies forced to treat resilience investments as risk-reducing, not expenditure

- Fossil fuel subsidies sharply reduced, with savings earmarked for international transfers

Outcome: The bill is shared more fairly. Global North pays more in money; Global South pays less in human suffering.

Key Features:

- Climate finance rises in absolute terms but remains far below needs

- Loss & Damage remains largely symbolic; most support is loans and projectised grants

- Countries continue to borrow after disasters; IMF programmes proliferate

- "Climate conditionality" added to existing debt conditionality

- Adaptation remains underfunded; extreme weather creates serial fiscal crises

Outcome: The planet burns slowly and unevenly. The system survives on the back of increased inequality, more migration, and periodic eruptions of anger.

Key Features:

- Repeated shocks and inadequate support cause multiple climate-vulnerable states to default

- Political systems radicalise; movements reject international lenders as illegitimate

- Regions experiment with alternative payment systems and commodity-backed arrangements

- Climate diplomacy fractures; trust in multilateralism collapses

- Geopolitical disorder: capital controls, sanctions, trade wars, proxy conflicts over water and resources

Outcome: The burning planet is paid for in geopolitical disorder, fragmentation, and violence.

What the Global South Can Demand

The Global South is not powerless in this story. But influence requires coherence and specificity. Five pillars of a more assertive agenda:

Climate-linked debt architecture: Push for automatic debt service suspension after major climate disasters, modelled on state-contingent clauses. Scale up debt-for-climate swaps with clear domestic accountability. Advocate for a standing facility under the IMF or a new institution explicitly designed to restructure debt in climate-vulnerable states on favourable terms.

A serious Loss & Damage mechanism: Demand multi-year, rules-based contributions from high-income emitters, ideally linked to historical responsibility and current emissions. Insist on grant-based support, not loans. Embed fast-disbursing parametric instruments to avoid bureaucratic delays.

Fair climate credit and rating practices: Pressure multilateral development banks and credit rating agencies to treat adaptation and resilience investments as risk-reducing assets, not expenditure. Develop alternative Southern-led risk metrics that integrate social and climate resilience.

Just industrial policy: Negotiate for local value-addition in green supply chains (smelting, processing, component manufacturing), not just raw mineral extraction. Use regional blocs—AU, ASEAN, Mercosur, CARICOM, SADC, the Indian Ocean Rim Association—to bargain with major buyers. Demand technology transfer and open standards in critical areas.

Regional risk pools and solidarity: Expand and deepen regional risk pools (such as existing Caribbean and African facilities) to share climate risks across countries. Create regional "resilience funds" capitalised by a mix of SDRs, sovereign wealth funds, and multilateral contributions.

What Works: Success Stories from Properly Funded Adaptation

The vulnerability economy is not inevitable. When adaptation receives adequate finance and political commitment, it works. These examples prove that the challenge is not technical impossibility but political will and resource allocation.

Bangladesh Cyclone Preparedness Program: In 1970, Cyclone Bhola killed 300,000-500,000 people—one of history's deadliest natural disasters. By 2020, Cyclone Amphan, of similar intensity, killed 26 people in Bangladesh. The difference: a comprehensive early warning system, 4,000 cyclone shelters, 76,000 trained volunteers, and coastal embankments. Total investment over 50 years: approximately $10 billion (national budget plus donor support). Lives saved: hundreds of thousands. The system demonstrates that even a low-income country can build resilience when resources are available and planning is sustained.

Ethiopia's Productive Safety Net Programme (PSNP): Launched in 2005 with World Bank and donor support, the PSNP provides predictable cash transfers and employment to 8 million Ethiopians in drought-prone areas. Cost: approximately $500 million annually. Impact: households receiving support are 1.3 times less likely to sell productive assets during droughts, and children in beneficiary households are significantly less likely to be stunted. The programme is not perfect—it struggled during the 2022 drought and Tigray conflict—but it proves that social protection can break the cycle of climate shock → asset depletion → deeper poverty.

Netherlands-Bangladesh Delta Plan: A €2.5 billion partnership (2014-2030) between the Netherlands and Bangladesh addresses river flooding, coastal erosion, and water management in the world's largest delta. The plan integrates infrastructure (polders, embankments), nature-based solutions (mangrove restoration), and community planning. Early results show reduced flood damage in pilot areas and improved agricultural productivity in protected zones. The key: long-term commitment, technology transfer, and joint financing where the vulnerable country is not left to bear all costs.

Caribbean Catastrophe Risk Insurance Facility (CCRIF): Established in 2007, CCRIF is a parametric insurance pool covering 20 Caribbean and Central American countries against hurricanes, earthquakes, and excess rainfall. When a triggering event occurs, payments are made within 14 days—no lengthy claims process. Total payouts 2007-2023: $285 million across 55 events. The facility is not a complete solution (coverage limits are modest), but it proves that regional risk pooling can provide fast liquidity after disasters, reducing reliance on emergency borrowing. Similar mechanisms now exist for Africa (ARC) and the Pacific (PCRAFI).

| Programme | Investment | Key Outcome | Cost-Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh Cyclone Preparedness | ~$10B over 50 years | Cyclone deaths: 300,000+ (1970) → 26 (2020 similar storm) | Every $1 spent saves $3-10 in disaster losses |

| Ethiopia PSNP | ~$500M annually | Households 1.3x less likely to sell assets; child nutrition improved | Breaks poverty trap; $1 generates $1.50-2 in long-term benefits |

| Netherlands-Bangladesh Delta Plan | €2.5B (2014-2030) | Flood damage reduced 30-50% in pilot areas; ag productivity up 20% | Estimated $4-6 return per $1 invested |

| Caribbean CCRIF | $285M payouts (2007-2023) | 14-day liquidity post-disaster; reduces emergency borrowing | Avoids high-interest debt; preserves fiscal space |

| Vietnam Mangrove Restoration | $1.1M (12,000 hectares) | Saves $7.3M annually in dyke maintenance; storm surge protection | $1 → $7 annual return + biodiversity + fisheries |

| Kenya Index Insurance (KLIP) | Donor-subsidised premiums | Livestock losses reduced 20-36%; no distress sales | $1 premium → $2.50-4 avoided losses |

Answering the Question

So: who pays for a burning planet?

Right now, the answer is empirically clear. A farmer in Malawi whose maize fails under erratic rains. A garment worker in Pakistan whose factory is flooded, whose wage disappears, and whose family takes out a loan to survive. A nurse in Mauritius paying more for imported food as currency depreciation and climate-linked shocks feed inflation. A child pulled from school in coastal Bangladesh after cyclones destroy the family's home twice in a decade. A young graduate from Lagos or Colombo who sees no future after repeated crises and risks their life on a migration route.

They pay first. Then their governments pay, through debt. Then, if the politics allow, some of that debt is relieved or restructured—often too late.

High-income countries pay something—but far less than the scale of their responsibility and capacity. Their voters pay modestly higher energy prices, fund green subsidies through domestic taxes, and face occasional climate disasters of their own. But structurally, they still sit at the creditor end of the global climate chain.

The moral claim is simple: in a burning planet, those who lit the fire and profited from it should pay more of the bill than those whose homes are now burning. The economic logic points the same way. Under-investing in resilience and over-relying on debt in vulnerable states is not only unjust; it is macro-economically destructive. It creates chronic instability, sovereign risk, and migration pressure that will spill across all borders.

The political challenge is whether the world can admit this openly—and design mechanisms that act accordingly. If it cannot, the vulnerability economy will deepen. Climate risk will harden into a caste system: nations locked into permanent repayment, communities locked into recurring loss, generations locked into diminished futures. If it can, the question "who pays?" becomes less poisonous. The answer shifts from "the poorest, forever" to something closer to shared responsibility. A burning planet will send a bill either way. The only real choice is whose name is on the invoice—and how much blood, rather than money, is used as the ultimate currency of payment.

Add comment

Comments